"The best qualification of a prophet is to have a good memory. " -Marquis of Halifax

I've been told more than once in my life that I think too fast. It's a valuable skill. I can look at large patterns of information and infer patterns that lead me to provable conclusions. I'm not always right in these inferences, but even when I'm wrong, the initial hypothesis almost always leads me to very valuable results.

The NBA Cap situation has been triggering my spidey sense for a while. Gordon Hayward got the max. Chandler Parsons got the max. Kyrie Irving got the max. To the casual fans, these seem like terrible and/or indefensible deals. Patrick even walked you through how (in general) free agency signings are awful.

Most years, they would both be right. However, as I briefly explained in the Free Agent value post, the financial landscape of the NBA is about to completely change. The NBA is poised to sign a new national television deal for the 2016-17 season that should make everyone involved with the sport of basketball much, much richer. Salaries will rise to match this new projected influx of cash (because salaries are fixed at 50% of "basketball related income") and all of a sudden, longterm deals signed before the advent of the new TV contract will be discount deals.

Functionally, any contract signed in this offseason longer than two years is a discounted contract. There is a reason Lebron has an opt out on his new Cavaliers contract. To quote:

Rich Paul of Klutch Sports is James' agent, and Mark Termini leads contract negotiations for the Klutch.

James could have taken a four-year contract worth more than $88 million from the Cavs. But he now will be able to negotiate a better contract in two years and also has the choice to opt out after one season to renegotiate next summer. Player options only can come before the final season of a contract, another reason for the two-year deal.

Lebron's agent realized that by having the opt outs, he can guarantee that his client gets the maximum dollar amount for his services regardless of the growth of the tv deal. Younger players signing "max" deals are not really doing that since, because of the way the CBA is structured, they are locked in to 2014-15 rates -- which we know will be significantly lower than projected salary rates in future rates.

You'll note that if you read any of the coverage that's out there, there aren't a lot of specifics about the the TV deal and what the actual impact of it will be. No one is exactly sure what the new NBA fiscal realty will look like for the 2016-7 season. Even the most notorious of the stat geeks out there, Nate Silver, is not quite there in estimating the real value of a win.

Let's see what we can do to correct that. Here's my (hopefully) concise and comprehensive guide to coming NBA Salary Cap Apocalypse.

We start with the central truth that when attempting to divine the shape of the future, the past is always prologue. We want to look for similar scenarios and situations to inform our prediction. The more data we have, the better our predictions will be. In this particular case, If we want to predict the shape of the new NBA tv contract, we should look at the most recent contract negotiations for the four major US sports.

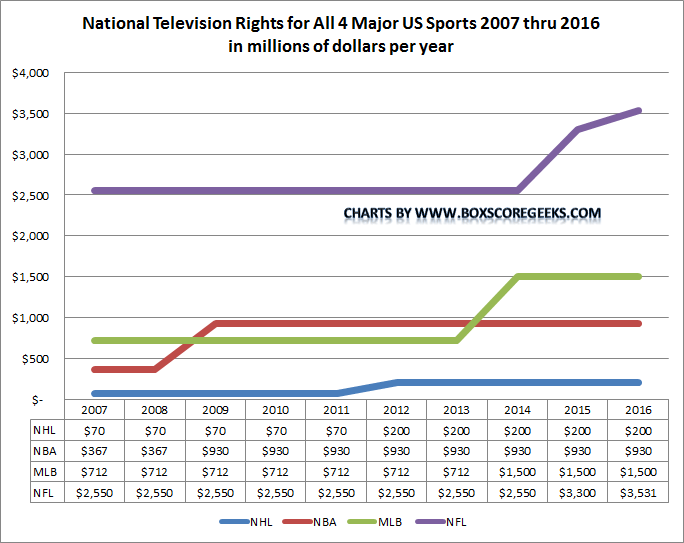

That charts the national TV revenue for the NHL, NFL, MLB and NBA from 2007 through 2016, when the next contract comes due. You'll note a significant rise for all the deals. Let's walk through them chronologically:

- 2008: NBA extends it's previous television deal for eight years with Disney(ABC/ESPN) and TimeWarner(TBS/TNT) through the 2015-6 season. Annual revenues jumped from $367 million to $930 million annually, an increase of 2.54 times.

- 2011: NHL signs a new deal with NBC through the 2020-21 season. Annual revenues jumped from $70 million to $200 million annually, an increase of 2.84 times.

- 2011: The NFL signs a nine year deal with Fox, ESPN and TBS from the 2014-15 to the 2022-23 season. The NFL deal is a little different than the other deals on this list as it sees a yearly increase as opposed to a straight one time increase. Annual average revenues jumped from $2550 million to $4392 million annually, an increase of 1.72 times.

- 2012: MLB signs a new eight year deal with Fox, ESPN and TBS from the 2014 to the 2021 season. Annual revenues jumped from $712 million to $1500 million annually, an increase of 2.11 times.

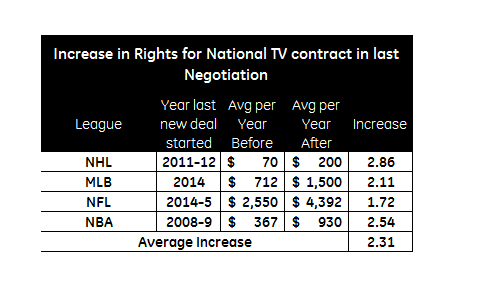

If we tabulate these contracts it looks like so:

Major sports TV contracts that have been negotiated over the past seven years have seen an average rise in per-year income of 231%. We can use that to project an annual national TV Revenue number for the NBA.

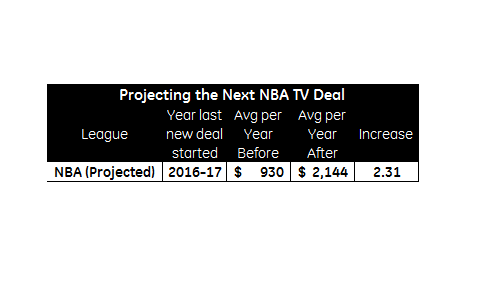

Using that 2.31 ratio, we can predict an average annual number of about $2.144 Billion for the total of all the contracts that the league signs with it's television partners.

Given the current competitive environement for live sports television rights and the propagation of new outlets looking to make a mark (NBC Sports, Fox Sports 1), I think this is a very conservative estimate for the contract. Consider that this is the first major sports contract that has gone to bid since the birth of the aforementioned competitors for ESPN from NBC Universal and News Corp and, as I mentioned in the Sloan conference review piece, Google is circling the old media companies like a shark that smells blood in the water. This could get very interesting very quickly.

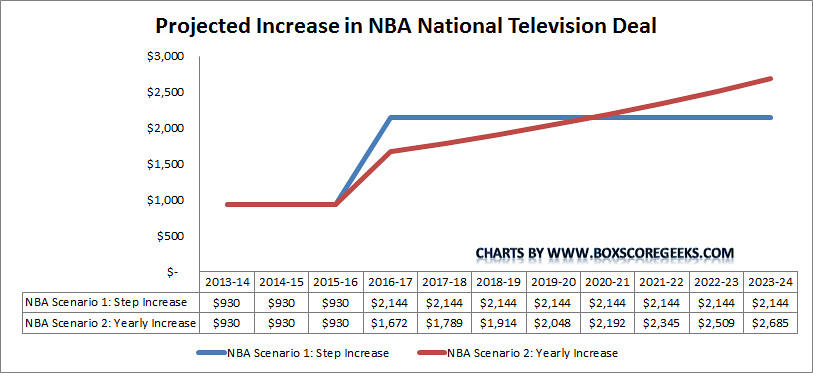

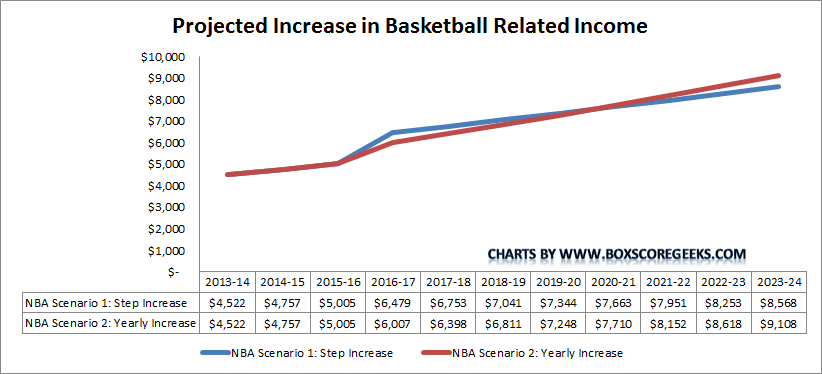

I would not be shocked by a number in the $3.5 billion per year range. But we'll keep this within the range of very likely outcomes. $2.144 Billion a year is our number. There are two flavors for this number though. Does the NBA take a step increase like the NHL, MLB in their last deals, or do they negotiate a yearly increase like the NFL?

It's a long term versus short term choice. The step increase has the effect of raising the value of franchises, total earnings and player salaries to the maximum possible value for the 2015-16 season. If you're in it for the short term (you're an owner looking to sell, you're a player with a limited earnings window), this is the best possible deal. The yearly increase takes less money to start but by increasing year to year ends with a higher salary, earnings and franchise value from the 2021-2 season on. I'd personally go with the yearly increase if I were advising the owners. I suspect they'll take the stepwise increase. I've previously noted that fiscal restraint and foresight are not prerequisites for owning an NBA team. Nevertheless, I will take the time to walk you through both scenarios.

Let's translate this into earnings, which in NBA-land means Basketball Related Income (BRI) . Larry Coon's excellent and indispensible CBA FAQ defines BRI as follows:

Basketball Related Income (BRI) essentially includes any income related to basketball operations received by the NBA, NBA Properties1, NBA Media Ventures, or any other subsidiaries. It also includes income from businesses in which the league, a league entity or a team has an ownership stake of at least 50%. BRI includes:

- Regular season gate receipts, minus taxes and certain charges including those related to arena financing

- Broadcast rights

- Exhibition game proceeds

- Playoff gate receipts

- The value of all complimentary tickets, minus "excluded complimentary tickets" (1.6 million tickets in 2011-12, increasing by 50,000 each season thereafter)

- Novelty, program and concession sales (at the arena and in team-identified stores within proximity of an NBA arena)

- Parking

- Proceeds from team sponsorships

- Proceeds from team promotions

- Arena club revenues

- Proceeds from summer camps

- Proceeds from non-NBA basketball tournaments

- Proceeds from mascot and dance team appearances

- Proceeds from beverage sale rights

- 40% of proceeds from arena signage

- 40% of proceeds from luxury suites

- 50% of proceeds from arena naming rights

- 50% of the proceeds from team practice facility naming rights

- Proceeds from other premium seat licenses

- Proceeds received by NBA Properties, including international television, sponsorships, revenues from NBA Entertainment, the All-Star Game, and other NBA special events.

Some of the things specifically not included in BRI are proceeds from the grant of expansion teams, fines, all forms of revenue sharing, interest income, and the sale of assets.

The current split of BRI per the Collective Barganing Agreement (CBA) is 50/50. The owners and players split the pot evenly. The owners do have some very significant other mechanisms to earn a profit (I've explained this before), such as the Roster Depreciation Allowance and the rising price of the franchise, but for payroll purposes, the BRI is all that matters.

If a player signs a five year deal this offseason, by the end of that deal the BRI will have risen by either 48% or 43%. That means that the actual average salary that must be paid to the players as specified per the CBA must have risen by the exact same amount. If I told you this was happening where you worked, would you sign a fixed salary five year contract particularly, since you might not get another one?

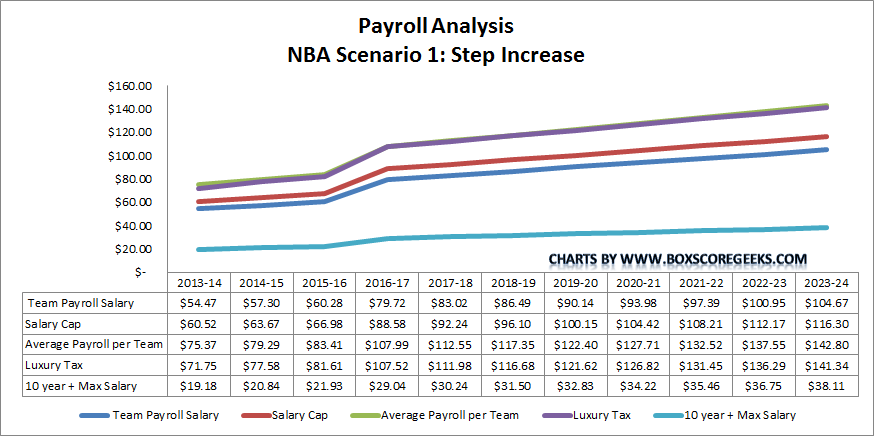

Let's look at the payroll scenarios for both cases. First we look at the step increase.

In this scenario we see the cap rise from the $67 million range in 2015-16 to the $89 million range in 2016-17 with a player salary max at around $29 million. This basically means that every single NBA team should be able to fairly easily make a max contract offer to a Player in the 2016 offseason. Durant, Love, Lebron will be able to pick and choose wherever they want to go and there will be some horrendous contracts given out -- Horrendous!

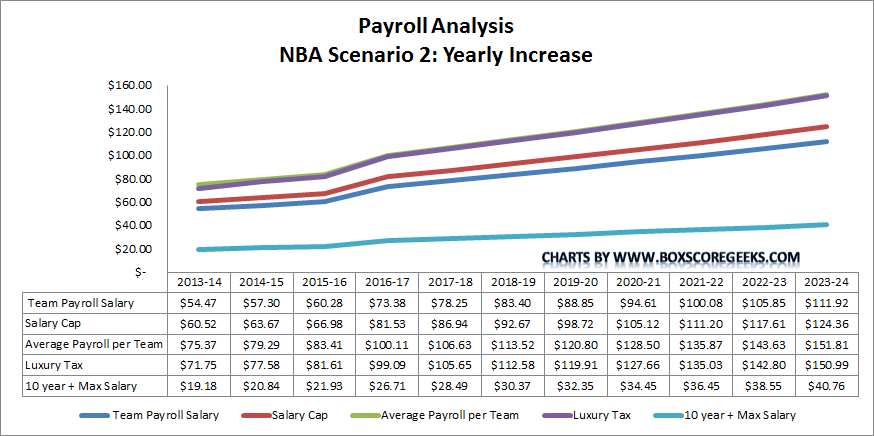

Now we look at the yearly increase.

This scenario is somewhat more sedate. The jump is from $67 million to $81.5 in that 2016 offseason. Only around $14.5 million extra to throw around. The max salary only moves to the $26/27 million a year range. However, I still expect a majority of teams to sign max contracts. It'll still make this offseason look like a flag football game by comparison.

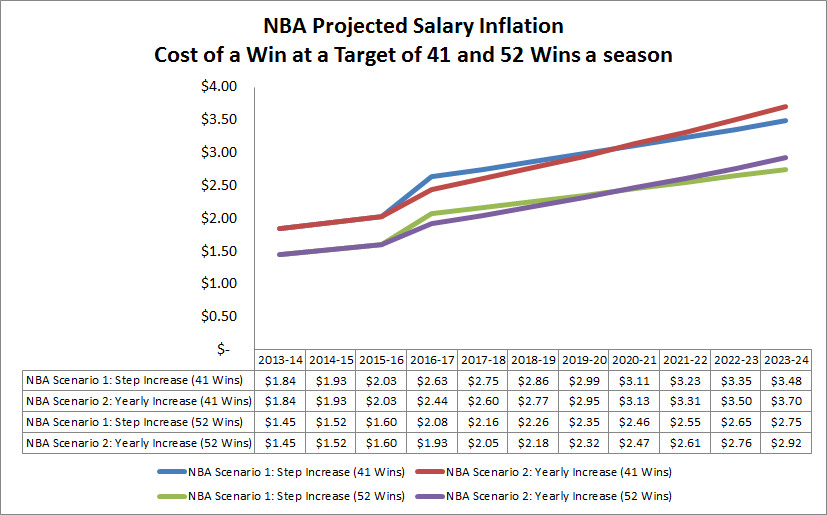

To further illustrate the price inflation, let's look at the price of a win.

The chart is calculates the fair price of a win two ways. The first is taking the total salary owed to the players (half the projceted BRI) and dividing by the total number of wins in a regular season (41 wins time 30 teams =1230 wins). This is a very player-friendly approach as it assumes all wins are payed for equitably and it generally works out as a rule of thumb for free agents because players under rookie contracts are grossly underpaid. A more aggresive approach targets 52 wins as the threshhold for a contender and uses that as the benchmark for contracts. I provided both as a good fuzzy guidepost of where the price of wins should.

Please note that, for the 2013-14 season, the price of a win was somewhere between $1.45 million and $1.84 million. At the end of any five year contract signed in this offseason (2018-19 season), that range will sit between $2.18 and $2.86 million. That's an increase of 50-55% in the fair price to be paid for a win. To illustrate, if our old friend Carmelo Anthony plays on average 2500 minutes at an average Wins Produced per 48 of between .100 and .150 over the course of his $125 super max five year extension (a friendly, if not outlandish assumption) we will expect the following production:

- Minutes: 12,500

- Wins Produced: between 26 and 39

- Value of those wins (using highest win value): between $63 and $95 million

So even signing Melo to the max, a contract that would have had me screaming bloody murder a few years back is only on the level of mild incompetence (and is mitigated by the Knicks crazy cash revenue stream).

I can't however explain or justify the Ben Gordon to Orlando contract. Some things are just incompetence.